|

Tulane and Race Relations

|

|

|

Tulane and Race Relations

|

|

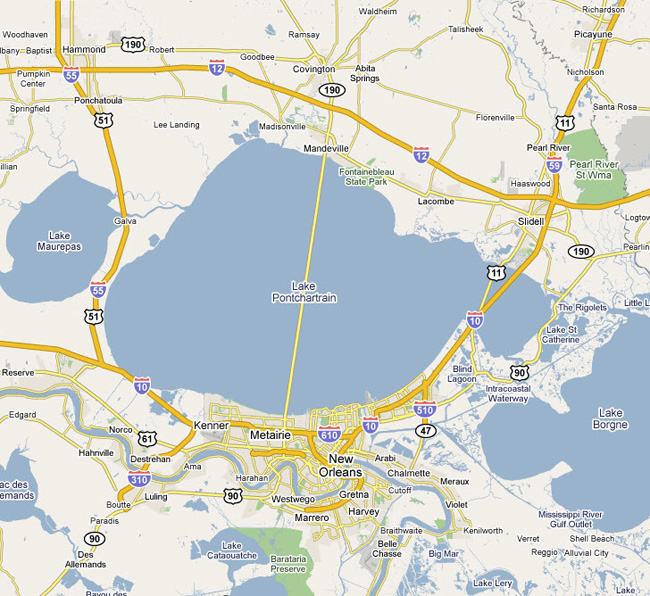

As an influential Louisiana politician and bond attorney for the $56.7 million Lake Pontchartrain Causeway that connected the predominantly white enclaves of Jefferson and St. Tammany Parishes in Louisiana,* Frank Burton Ellis may have anticipated the role that the new toll bridge would play in facilitating white flight out of New Orleans during the tumultuous period of public school integration in the 1960s. He strongly opposed desegregation.

*Parishes in Louisiana are equivalent to counties in all other states.

Like many of his family members whose careers took them to New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Washington, D.C., Judge Frank Burton Ellis was born in Covington, the parish seat of St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, whose southern boundary forms the major shoreline of Lake Pontchartrain's Northshore region. He died in New Orleans in 1969 and was buried in the Ellis Cemetery outside the city of Amite, the parish seat of Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana.1-6 The Ellis family has been associated with the judicial history of this area since creation of the parishes,7 and Ellis' political decisions often reflected the influence of his lineage.8

In the Beginning

In 1810, President James Madison sent Governor W.C.C. Claiborne to claim the territory known then as the West Florida Parishes for the state of Louisiana,9 and from those lands the legislature on April 24, 1811 created what is now St. Tammany Parish.7 On July 18 of that same year, Thomas Cargill Warner was commissioned as first judge of the parish. He and his wife, Tabitha F. Cargill, had 13 children, and their daughter, Tabitha Emily Cargill, married Ezekiel Parke Ellis, the great-grandfather of Frank Burton Ellis. Thus began a tradition in law that has continued for seven Ellis generations.7

Ezekiel Parke Ellis was elected clerk of court, and following that he was elected to a term in the state legislature. Ezekiel and his wife, Tabitha Emily, had eight children, and after living in Clinton, Louisiana, the family moved to Amite where Ezekiel set up a law practice. Subsequently, Ezekiel was elected judge of the 6th District Court which held jurisdiction over the parishes of Tangipahoa, St. Tammany, and Washington.7

Ezekiel and Tabitha's sons all carried on in the judicial tradition and were lawyers, judges, district attorneys, doctors, Confederate soldiers and officers, state representatives and senators, U.S. representatives and senators, and they generally were politically and professionally active in St. Tammany and Tangipahoa parishes and later in Orleans Parish.7 Ezekiel's son, Ezekiel John Ellis, the grandfather of Frank Burton Ellis, was born in St. Tammany Parish and died in Tangipahoa Parish. Ezekiel John's son, Harvey Eugene Ellis, the father of Frank Burton Ellis, was born in New Orleans and moved to Covington, where he set up his law practice and founded a bank that survived change and still exists.7 In 2008, members of the extended Ellis family still lived in Covington, including Judge Frederick Stephen Ellis, the great-great-great grandson of Ezekiel Parke Ellis through Ezekiel's eldest son, Thomas Cargill Warner Ellis.10

Connecting the Dots

The idea of a bridge across Lake Pontchartrain connecting New Orleans and the Northshore11 to provide access to what is now St. Tammany Parish dates back to the early 19th Century.12 Bernard Xavier Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville (Marigny),13 a member of a prominent Louisiana family and owner of one-third of the city of New Orleans, purchased considerable amounts of land on the Northshore in 1834, which included present day Mandeville in St. Tammany Parish.14,15 The oldest inhabited locality, Mandeville was incorporated in 1840 after Marigny established it as a fashionable resort town.16 Covington, the seat of the St. Tammany Parish government had been incorporated in 1816.17

LAKE PONTCHARTRAIN AND ENVIRONS Showing the Causeway toll bridge connecting Metairie in Jefferson Parish with Mandeville in St. Tammany Parish (Source: Google Maps, http://maps.google.com/...)

(Source: Google Maps, http://maps.google.com/...)

LAKE PONTCHARTRAIN IN LOUISIANA (LEFT) AND THE SURROUNDING PARISHES (RIGHT) Marigny used the area for relaxation and as an escape from his commerce in New Orleans, and he invited and entertained guests and friends there. As visitors from New Orleans discovered the fresh waters, clear air, and beauty of the area, opportunities for hotels and restaurants arose. Cottages, shops and recreation facilities followed, and vacationers and business people alike would traverse the lake by boat and later circumvent it by railroad to enjoy and exploit the rich amenities of the Northshore.14

Travel by steamboat began in 1815,16 and Marigny's ferry service continued into the

mid-1930s .12 Another ferry, the steamboat Cape Charles, built originally for use elsewhere, was acquired by the East Louisiana Railroad around 1895 and used on Lake Pontchartrain between New Orleans (at Spanish Fort)16 and Mandeville for a period of about two years.18At the end of the 19th Century, railroads began to flourish and Mandeville became an important center for commerce.15 By the

mid-1920s , the need for improved access to the Northshore from New Orleans had become pressing, and several unique proposals for spanning Lake Pontchartrain were conceived.12Finally, in 1948, the Louisiana Legislature created what is known as the Causeway Commission (officially, the Greater New Orleans Expressway Commission)19 which deliberated over the best means of connecting the New Orleans metropolitan area with the Northshore and later supervised construction of the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway.12,20 Frank Burton Ellis, who had been a member of the Louisiana Senate from 1940 to 1944 and was its president

pro-tem , is credited with masterminding the financing of the24-mile bridge , which was critical to its construction.21 As a political operative, he was close to Governor Earl K. Long and was appointed bond attorney for the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway.5Following his unsuccessful campaign in 1944 for Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana, Ellis moved to New Orleans to practice law and further his political ambitions in the Democratic Party. Ellis was active in the presidential

re-election campaign of Harry Truman in 1948,4,5 and he directed the successful Democratic presidential campaigns that delivered Louisiana's electoral votes to Adlai Stevenson in 1952 (who nevertheless lost the presidency to Dwight Eisenhower)22 and to John Kennedy in 1960 (who defeated Richard Nixon).23 Ellis' personal drive24 and his political and family connections accorded him great influence among Louisiana's powerful elites. His passion and stewardship over the Causeway project were largely responsible for its successful completion.24In 1956, the initial

two-lane Causeway was opened at a cost of$30.7 million , and in 1969 a second, paralleltwo-lane span opened at a cost of$26 million .12 Although the bridge is usually touted as connecting the New Orleans metropolitan area with the Northshore, its southern terminus is not the city of New Orleans itself, but rather the predominately white suburb of Metairie in neighboring Jefferson Parish. Many prominent and influential families who conducted their social, professional and business affairs in New Orleans also had residences in Covington or Mandeville while still maintaining homes in New Orleans. The Causeway was a welcometime-saver for these families.Conduits for White Flight

Hale Boggs, a U.S. Representative from Louisiana, was born in Long Beach, Mississippi but grew up in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana. He served in Congress from 1941 to 1943 and from 1947 until his death in 1972.19 As House Majority Leader and member of the Ways and Means Committee, Boggs was in a pivotal position to deal with the problematic issue of financing highway construction, and he drafted the mechanism for funding legislation that he had worked on with Rep. George Fallon to create the interstate highway system.11,19 In 1956, once Boggs had incorporated the concept of a "Highway Trust Fund," the interstate system was able to go forward.11

During the 1950s, substantial numbers of white residents were already leaving New Orleans for recently developed communities in Jefferson Parish, primarily Metairie.25 However, following construction of the Causeway in 1956 and the designations in 1957 of Interstate 12 to the north and Interstate 10 to the east side of Lake Pontchartrain, respectively,26,27 whites began to relocate to St. Tammany Parish in large numbers.9

The improvements in regional highways allowed suburban developments to lure

middle-class residents from New Orleans. But racism was primarily responsible for pushing white residents across parish lines as the city underwent desegregation of schools and public accommodations.25 To the extent that growth of the Northshore at the expense of New Orleans was a direct result of opening the Causeway raises a question of whether Ellis anticipated, or even intended that outcome.14

Data from the U.S. Bureau of the Census28 except for year 2000, which was compiled from: New Orleans,29,30 Jefferson Parish,31 St. Tammany Parish32 and Tangipahoa Parish.33

Data from the U.S. Bureau of the Census28 except for year 2000, which was compiled from: New Orleans,29,30 Jefferson Parish,31 St. Tammany Parish32 and Tangipahoa Parish.33Contributing to the loss of population from New Orleans – aside from the unrest that accompanied desegregation of the public schools and public accommodations – was the loss of manufacturing jobs, which changed the direction of the economy toward the service industry, particularly tourism.

The Causeway was a significant advantage for those in the business sector who would now have convenient access to both New Orleans and the Northshore and could raise their families across the lake and continue to work in New Orleans. The reduction in driving time is estimated to be about 50 minutes when compared to whether one traveled around the lake via the north route or the east route,12 and the improved access helped spur the growth of Mandeville and the surrounding area as a suburban commuter community for people working in New Orleans, a trend that increased in the 1980s and 1990s.34

Expansion into St. Tammany Parish involved even the city's major private employer, Tulane University, which has deep roots in New Orleans where its main campus is located. The Tulane National Primate Research Center (formerly, the Delta Regional Primate Research Center), was opened in November, 1964 in Covington. It is the largest of the eight centers that make up the National Primate Research Center Program, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).35-38 Dr. George Burch of Tulane University was chairman of the NIH planning committee that helped plan the development of the regional primate centers.35-38

The Primate Research Center has grown steadily since its inception and has involved a major investment of public resources. In December 2008, a Regional Biosafety Laboratory costing

$27.5 million was dedicated. A$21 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) helped pay for the new laboratory. That, together with a new$9.5 million animal research facility, is expected to add 60 new jobs to the 280 people already employed.35-38 Such expansion contributes substantially to the economic growth of the suburbs and helps draw educated and skilled workers away from the New Orleans area. In 2010, Tulane proposed a rezoning change that would permit the expansion of its medical research facilities at the center.39Additional plans for other biomedical projects will continue to further the growth of St. Tammany Parish. For example, by late 2010, a

multi-million dollar forensic science center is projected to be opened on 40 acres just south of a site where the parish is planning a "university square" campus for colleges and anadvanced-studies high school.40,41 A temporary DNA laboratory that opened in September 2007 is already receiving national and international accreditation from the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors.42 When it is completed, the laboratory should add many new jobs to the St. Tammany workforce.Miscalculations and Revelations

In the early 1960s, white migration to suburban parishes represented only one of several major concerns in New Orleans. During this era, the Port of New Orleans was in decline from the competition of newer, more technologically advanced port cities.43 The Port and Dock Board attempted a major overhaul of infrastructure and spent more than

$128 million on expansion and construction. It also convinced the city, state, and federal governments to dig the MississippiRiver-Gulf Outlet (MR-GO ) at a cost of an additional$120 million to create a direct route from the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans.U.S. Congressman Hale Boggs had expected

MR-GO to be the largest single source of employment in the greater New Orleans area.44 However, in 1965 Hurricane Betsy inflicted more than$1 billion in damage to shipping interests when a wall of water was pushed into the Industrial Canal, and many doubted whether that would have occurred if therecently-finished MR-GO had not been constructed.45 Continued debates over the role ofMR-GO in increasing the vulnerability of New Orleans tohurricane-related flooding ultimately lead to the decision in 2008 to close the60-mile waterway.46,47Hurricane Betsy in 1965 capped a series of milestone events that had stirred social, political, and economic currents in New Orleans,48 and in 1967 New Orleans Mayor Victor Schiro and city councilmen appealed to Washington, D.C. for urban renewal funds which the federal government was then distributing to American cities.49

In Louisiana, a 1954 state law restricted federal renewal aid more stringently than in any other state. It was not until 1968 that the state legislature took action that would permit federal urban renewal aid in Louisiana cities,50 and in 1969 voters in Orleans Parish endorsed a plan that would allow urban renewal funds for the city51.

While waiting for these funds, New Orleans took advantage of federal funding for antipoverty programs in an attempt to promote economic development in poor communities by relieving poverty and empowering poor city residents. Community leaders had long complained that the large pool of unskilled labor discouraged companies from relocating to New Orleans.52 Thus, the primary initiative designed to spur economic development in poor neighborhoods was job training.53 The Concentrated Employment Program (CEP) that the city undertook, however, soon became a source of controversy as neighborhood activists accused CEP administrators of simply peddling promises of good employment to poor residents.54

In the end, only 2,149 workers graduated from the CEP program, and both black and white leaders agreed that, since most of the trainees were "Negro," they would only be eligible for "traditional Negro jobs" in a city still sharply divided by color.55 One Uptown New Orleans socialite explained the city's dismal public education system to a visiting friend: "Down here, we don't believe in education for the masses. You don't need a college degree to fold sheets and plump pillows."56

As the dwindling urban population and burgeoning suburban development became apparent in the 1960s, city leaders recognized that growing economic stagnation required measures that ultimately led to the development of the tourism industry.30 J. Mark Souther of Cleveland State University argued that "an unlikely coalition of civil rights activists, tourism interests, municipal officials, and a small segment of New Orleans's

old-line social establishment adopted atourism-related rhetoric to counter the city's dominant discourses of racist resistance to change," and by the late 1960's, New Orleans's white leaders agreed that they could no longer countenance overt racial discrimination if New Orleans was to maintain a favorable tourist image.57 By 2001, tourism, which is included in the U.S. Census Bureau's service category, was New Orleans' biggest industry, making up the largest proportion(47 percent) of the area's workforce.58Public School Desegregation

Before the Civil War, teaching a slave to read was a crime in Louisiana, and free black children were barred from public schools. Many free black children, however, were educated in Catholic or private schools.58 After the Civil War, Republicans (Lincoln's party) engineered the rewriting of the state Constitution to require integration in the schools. But the mandate was ignored until the state legislature in 1870 passed an act that imposed severe penalties upon any person refusing admission to any public school of the state to a pupil on account of "race, color or previous condition."60 Republicans set up new school boards in New Orleans and obtained a court ruling that would give them control over spending. On November 21, 1870 the state district court ordered New Orleans schools to integrate.59

Nevertheless, enforcement of the law was resisted, and "colored children" were denied entrance by direction of the city school board. Even those few "obnoxious classes" that were formed were required to withdraw as a result of a concerted movement of "large companies of parents" who visited the schools and caused "great excitement."60 The "colored children" were placed back in their own schools, and as of 1893 there were no plans of a general nature to mix the races in New Orleans' public schools.60 William O. Rogers, Superintendent of the public schools in New Orleans in

1865-1870 and1877-1884 ,61 is credited with the "energy, tact and good judgement" for this "success" of the city's schools.60Rogers, who had been an officer in the Confederate Army,62 resigned as superintendent in 1870 in protest over Board of Education Rule No. 39, passed April 8, 1870, which admitted "colored pupils" to white schools in accordance with new state laws and which aroused bitter feelings of opposition in New Orleans.63 Rogers then became founder of a new parochial school system for whites that was supported by the Presbyterian churches. He returned to administer the public school system in 1877 when the "Carpet Bag" government in Louisiana came to an end.63 Rogers became a charter member (

1882-1884 ) and Secretary of the Board of Administrators of the Tulane University of Louisiana. He was also Tulane University Librarian and served as Tulane's Acting Second President (1899-1900 ).62In 1871, in response to several instances of integration, a reporter for the Daily Picayune wrote that "the outrageous work" of integration had begun.59 In prior years, the Daily Picayune (forerunner of the

Times-Picayune ) also ran advertisements seeking to sell slaves or find runaways.64Historian Roger Fisher studied those early attempts at integration as part of his doctoral work at Tulane University and concluded that "white resistance to school integration in the 1870's was mostly responsible for explosive growth in the city's parochial and private schools."59 Fischer found that private schools in the city increased from 10 in 1868 to 91 in 1871, the first year of racial mixing in the public schools. By

mid-1874 , nearlyone-third of the city schools hadracially-mixed classes.59 However, after September 14, 1874, when the White League defeated the Republican militia at the Battle of Liberty Place, many black students were forced from integrated schools.59Following the withdrawal of Union troops in 1877, white Democrats reclaimed control of the state and the old order was largely restored.59 In 1884, U.S. Senator Randall Lee Gibson, a former Confederate general, and philanthropist Paul Tulane succeeded in privatizing the public University of Louisiana as the Tulane University of Louisiana and dedicating it to the education of "young white persons in the City of New Orleans."65

The Extended Debate

In more recent times, a second migration mostly of white people from New Orleans to the suburbs started in the

mid-1950s , and although there are varied reasons behind this movement, they are chiefly grounded in racism. A major motivation of those who relocated was to ensure that their children would not have to go to school withAfrican-Americans .66 Nicholas H. Carter, in his undergraduate thesis for the Department of History at Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts observed that public school integration contributed heavily to this migration of white,middle-class families from Orleans Parish and had "tremendous consequences" for the development of New Orleans.42The case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), resulted in the landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that overturned earlier rulings going back to Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 by declaring that state laws that established separate public schools for black and white students denied black children equal educational opportunities.67 The unanimous decision, handed down May 17, 1954 by the Warren Court, stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." As a result, any local law that permitted racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This victory paved the way for integration and the civil rights movement.67

Judge James Skelly Wright, who served as U.S. District Court Judge from 1949 to 1962 for the Eastern District of Louisiana, played an important role in the struggle to desegregate schools in the New Orleans area. His first desegregation order was in 1951 for the Law School at Louisiana State University.68 About that same time, Tulane University installed separate water fountains so black employees would not have to bring their own cups to work.69 In 1956, Ernest N. "Dutch" Morial, a black attorney and 1954 graduate of Louisiana State University Law School, was denied permission by Tulane Law School to audit courses offered to practicing attorneys.70 He later became Mayor of New Orleans.71

As the 1950's drew to a close, many white families in New Orleans, panicked over what they saw as the imminent threat of

race-mixing in the public schools.59 Despite the Brown decision of 1954, it was not until 1962 that Judge Skelly Wright ordered the first six grades in all the city's public schools to be integrated. That same year, the Catholic schools of New Orleans were desegregated. The city's Audubon Park, which had been prohibited to all black people except for maids accompanying white children, was desegregated in 1963.72In keeping with its founding principles, Tulane University fiercely resisted attempts at integration through a lawsuit brought by two black students who were denied admission: Guillory v. Administrators of Tulane University of Louisiana, 203 F. Supp. 855 (1962). In that suit, Judge Skelly Wright ruled for the plaintiffs and against the university.73 However, Judge Wright, who became the target of intense community derision, was soon replaced by Judge Frank Burton Ellis who quickly overturned Judge Wright's rulings in response to Tulane's direct appeal.73 Eventually, however, the black students were admitted after Tulane was threatened with the loss of grant funding over its discriminatory policies.74 Five years later, the School of Medicine admitted its first black student.75

Judge Skelly Wright had first ordered the desegregation of New Orleans schools to begin on November 14, 1960. However, the local Citizens' Council called on white parents to boycott the desegregated schools on the day that three black girls, Gail Etienne, Tressie Prevost and Leona Tate, began first grade at McDonogh 19 School and Ruby Bridges entered William Frantz School. The black students were guarded by marshals while mobs of white parents shouted racial epithets and threats.76

Almost all white parents kept their children home during the first days of desegregation. The

Times-Picayune reported that only 40 of 467 white pupils remained at William Frantz through Monday.77 At the end of the week, no white families had children enrolled at McDonogh 19, and only three white families at William Frantz remained. Those white students were stoned and beaten up by former friends, neighbors and classmates, and their parents had difficulty with employment.76At the time of the 1954 Brown decision, the Orleans Parish school system had been

half-white andhalf-black . In the 1960s, school integration coincided with an exodus ofmiddle-class white families to the suburbs where developments were being built.76 Ten years after Bridges and the three other girls became the first black children to attend New Orleans public schools, more than70 percent of the students in the public school system were black.76By the 1970s, students were still leaving in large numbers for the surrounding parishes. The middle class took with them their "social capital and financial capital,"78 while the loss of population "drained the city of jobs, tax revenues, and political clout."79 By the

mid-1980s ,low-income black students comprised90 percent of the school district.78Continued federal monies were dependent on "

good-faith integration efforts," and this motivated the Orleans Parish School Superintendent in 1972 to order the desegregation of the faculty. Both black and white teachers protested. Veteran black teachers were displeased when they were replaced at their neighborhood schools by "less-senior " white teachers solely on the basis of race while many white teachers, unhappy with being transferred to predominately black schools, left the school system along with the white students. In the decade between 1965 and 1975, the population of white students dropped from 38,785(37 percent) to 18,733(20 percent) .79"As a new de facto segregation emerged, many predominantly black schools would become centers of ever more concentrated poverty."79 In New Orleans, while racial tensions remained high for many years, some school systems outside the city managed to keep their white schools

all-white as enrollments swelled with the children of families who were escaping the problems of the city.80"Racism against blacks played a role in the growth of a white Metairie beginning in 1960, when federal courts forced racial integration of public schools. The continued growth of Metairie at the expense of New Orleans' population continued in the 1980's, when crime was a leading motivation for the migration westward."81

Camille Zubrinsky Charles in 2005 defined the "white flight" hypothesis as a

long-standing explanation for residential segregation that posits that uncomfortable levels of racial integration motivate whites to leave their existing neighborhoods for new ones.82 Nicholas H. Carter, in his study of cultural explanations of poverty in New Orleans, found that white flight, an archetypal problem in urban America, contributed heavily to New Orleans' impoverishment between 1965 and 1980.83

Data compiled from various sources: New Orleans,29 Metairie,81 Mandeville,34 Covington,84 Jefferson Parish,85 St. Tammany Parish86 and Tangipahoa Parish.33

Data compiled from various sources: New Orleans,29 Metairie,81 Mandeville,34 Covington,84 Jefferson Parish,85 St. Tammany Parish86 and Tangipahoa Parish.33As late as 2007, the Jefferson Parish school system still had a

43 year-old desegregation case against it which had still not been resolved, even though nearlytwo-thirds of all public school districts in Louisiana still fell under federal court supervision to ensure a racial mix in schools.87In March 2007, the Jefferson Parish school system revised its "federal order to address inequalities,"78 and by August 2008 the district engaged in a sweeping transformation that encompassed new attendance boundaries and faculty exchanges. It created four specialty magnet programs and implemented a

$50 million capital plan that targeted structurally inferior schools on one of the two banks of Jefferson Parish.87 Yet as 2009 dawned, a federal judge in New Orleans rejected Jefferson Parish's proposed magnet school master plan as impeding that system's progress toward achieving a desegregated status.88The Outlook

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation that outlawed racial segregation in schools, public places, and employment.89 Nevertheless, 44 years after its passage, many problems remain unresolved. In 2006, Edmund W. Lewis, editor of the Louisiana Weekly, commented of New Orleans: "This is a city where the black masses are forced to endure what some have termed 'educational apartheid,' a process that maims the minds of tens of thousands of young people each year and prepares them for lives of servitude."90

Charles Steele, Jr., president, chief executive officer and leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, at its 50th annual convention held on July 2008 in New Orleans, said: "What we've discovered in New Orleans is that it's one of the most racist communities in this country."91 Steele observed that a violent environment in the city is created by rampant racial discrimination and few economic opportunities to escape the service industry and violence.91

In 2007, New Orleans was ranked as the city with the highest crime rates in the United States, and in 2008 it was named the murder capital of the nation.92,93 Clearly, the problems that plague New Orleans continue to frustrate those who have been perennially disfranchised as well as those who are dedicated to just and rational social reforms.

Meanwhile in 2008, increased traffic on the Northshore around Mandeville has prompted the Causeway Commission to widen roads in this area,94 and the commission is considering the construction of a third span across the lake.12 Inherent in these developments are continued demographic and economic consequences for the future of New Orleans.

Carl Bernofsky

Shreveport, Louisiana

January 15, 2009

Note

Political, genealogical and demographic data was assembled from sources considered to be reliable. Only a small sampling of the large amount of information available is cited. Please address corrections to the author at tulanelink@aol.com.

References

- "Amite City, Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amite,_Louisiana, accessed 12/07/2008.

- Submitted by Edie McKinney Talley, "Ellis Cemetery: Tangipahoa Parish, La.," LAGenWeb Archives, http://files.usgwarchives.org/la/tangipahoa/cemeteries/ellis.txt, accessed 06/24/2008.

- Inventory by Luana Henderson, "Appendix - Ellis Family Tree," Buck-Ellis Family Papers (Mss. 4820), Louisiana State University Libraries,

pp. 24-25 , http://www.lib.lsu.edu/special/findaid/4820.pdf, accessed 07/06/2008.

- "Index to Politicians: Ellis," Political Graveyard, http://political graveyard.com/bio/ellis.html, accessed 11/28/2008.

- "Judge Ellis Dies; Burial Set at Amite," The Morning Advocate, Baton Rouge, LA, November 5, 1969. Source: State Library of Louisiana, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, accessed 12/23/2008.

- "Ellis, Frank Burton," Judges of the United States Courts, http://www.fjc.gov/servlet/tGetInfo?jid=701, accessed 08/28/2008.

- Todd Valois, "7 Generations of Family Found Calling in the Law," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, July 7, 1992, Picayune Section,

p. 10H1 .

- Carl Bernofsky, "Judge Frank Burton Ellis (1907-1969): A Brief Biography and Selective Genealogy," Tulanelink.com, http://www.tulanelink.com/tulanelink/judgefrankellis_08a.htm, accessed 12/28/2008.

- "St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Tammany_Parish, accessed 12/11/2008.

- "Thomas Cargill Warner Ellis III," Death Notices & Guest Books, nola.com, http://www.legacy.com/NOLA/DeathNotices.asp?Page=Notice&PersonID=114484801. accessed 08/16/2008.

- "Welcome to Louisiana's I-12 Retirement District," Southeastern Louisiana University Business Center, http://www.lai-12retirement.org/, accessed 12/12/2008.

- "Lake Ponchartrain Causeway," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Pontchartrain_Causeway, accessed 11/23/2008.

- "Bernard de Marigny," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_de_Marigny, accessed 12/10/2008.

- "Welcome to the City of Mandeville," Mandeville, Louisiana, http://www.cityofmandeville.org See: Inside Mandeville - Mandeville Past and Present - Past, accessed 12/07/2008.

- "Mandeville on the Lake," Welcome to the City of Mandeville, Mandeville, Louisiana, http://www.cityofmandeville.org/view.cgi?action=view&page=626&i=102, accessed 12/10/2008.

- "Moments in Time: Exploring the History of the Lake Pontchartrain Basis," Lessons on the Lake, http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1998/of98-805/lessons/chpt10/index.htm, accessed 12/22/2008.

- "A Little Covington History," City of Covington, Louisiana, http://www.cityofcovingtonla.com/10hist1.html, accessed 12/26/2008.

- "1895~Cape Charles Ferry/Steamboat," From: New Orleans, Louisiana History~~Lake Pontchartrain, http://stphilipneri.org/teacher/pontchartrain/content.php?type=1&id=299, accessed 12/07/2008.

- Richard F. Weingroff, "The Battles of New Orleans - Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310)," Highway History, U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm, accessed 01/06/2009.

- Carl A. Brasseaux and James D. Wilson, Jr., Editors, "A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, Ten-Year Supplement 1988-1998,

Vol. I , The Louisiana Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Louisiana Studies of the University of Southwestern Louisiana (1999),pp. 78-79 , accessed 01/07/2009.

- "Louisiana Haymaker," Time Magazine, April 14, 1961, http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,872246,00.html, accessed 11/21/2008.

- "1952 Presidential General Election Results - Louisiana," USA Election Polls, http://www.uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=22&year=1952&f=0&off=0&elect=0, accessed 12/21/2008.

- "1960 Presidential General Election Results - Louisiana," USA Election Polls, http://www.uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=22&year=1960&f=0&off=0&elect=0, accessed 12/21/2008.

- "Lawyer for Defense: Frank Burton Ellis," The New York Times, New York, NY, January 24, 1961, http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FB0913FB3C5D1B728DDDAD0A94D9405B818AF1D3, accessed 12/14/2008.

- Nicholas H. Carter, Contesting Cultural Explanations of Poverty: Migration and Economic Development in New Orleans, 1965-1980, [PDF], A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, April 16, 2007,

96 pp. ,p. 90 .

- "Interstate 10 in Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstate_10_in_Louisiana, accessed 01/01/2009.

- "Interstate 12," History, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstate_12, accessed 01/01/2009.

- Compiled and edited by Richard L. Forstall, "Louisiana: Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900-1990," Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC 20233, http://www.census.gov/population/cencounts/la190090.txt, accessed 11/21/2008.

- "Orleans Parish: People & Household Characteristics," Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, http://www.gnocdc.org/orleans/people.html, accessed 12/02/2008.

- Kevin Fox Gotham, "Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans' Vieux Carre (French Quarter)," Urban Studies,

Vol. 42 ,No. 7 ,1099-1121 ,June 2005 , http://www.tulane.edu/~kgotham/TourismGentrification.pdf, accessed 12/08/2008.

- "2000 Population of Jefferson Parish, Louisiana," The Parish of Jefferson Census Information, http://www.jeffparish.net/index.cfm?DocID=1223, accessed 12/02/2008.

- "St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Tammany_Parish. accessed 12/01/2008.

- "Tangipahoa Parish: People & Household Characteristics," Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, http://www.gnocdc.org/tangipahoa/people.html, accessed 12/02/2008.

- "Mandeville, Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mandeville,_Louisiana, accessed 12/10/ 2008.

- "History," Tulane National Primate Research Center, http://www.tnprc.tulane.edu/history.html, accessed 12/12/2008.

- W. Richard Dukelow and Leo A. Whitehair, "A Brief Historyof the Regional Primate Research Centers," Comparative Pathology Bulletin, 27(3):

1-2 , 1995, Primate Info. Net, http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/research/dukelow.html, accessed 12/12/2008.

- Keith Brannon, "New $27.5 Million Tulane University Biosafety Lab Will Expand Research, Create Jobs," Tulane University News Release, December 5, 2008, http://tulane.edu/news/releases/pr_120508.cfm, accessed 12/05/2008.

- Benjamin Alexander-Bloch, "Primate Center Unveils Biosafety Lab - Facility Part of U.S. Plan to Fight, Plan for Bioterror Events," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, December 6, 2008, National, p. 01. See also: John Pope, "Tulane to Unveil Biosafety Facility- Regional Lab to Study Infectious Diseases," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, November 21, 2008, Metor,

p. 04 .

- Benjamin Alexander-Bloch, "Primate Center Decision Delayed - Neighbors Oppose Zoning Change," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, August 5, 2010, Metro, p. 01. See also: Benjamin Alexander-Bloch, "Parish Allows Go-Ahead On Levees - Work Will Improve Them South of Slidell," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, August 6, 2010, Metro, p. 01.

- Charlie Chapple, "Home, College Project Moves Forward - University Square Could Start in Spring," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, June 14, 2008, National,

p. 01 .

- "Week in Review," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, June 22, 2008, Slidell Picayune Section,

p. 01 .

- Charlie Chapple, "Unified Forensic Center Coming Soon - Facility Should Be Finished in 2010," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, December 13, 2008, National,

p. 01 .

- Nicholas H. Carter, Contesting Cultural Explanations of Poverty: Migration and Economic Development in New Orleans, 1965-1980, [PDF], A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, April 16, 2007,

96 pp. ,p. 17 .

- Ibid,

p. 18 .

- Ibid,

p. 19 .

- Sheila Grissett, "MR-GO Blamed for Levee Failures - Scientist Says Channel Exacerbated Flooding," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, December 19, 2008, Metro

p. 04 .

- Bob Warren, "MR-GO Closure Gets Go-ahead - Job to Finish Midway through Storm Season," The Times Picayune, New Orleans, December 17, 2008, Metro,

p. 01 .

- Nicholas H. Carter, Contesting Cultural Explanations of Poverty: Migration and Economic Development in New Orleans, 1965-1980, [PDF], A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, April 16, 2007,

96 pp. ,p. 25 .

- Ibid,

p. 28 .

- Ibid,

pp. 28-29 .

- Ibid,

p. 30 .

- Ibid,

p. 35 .

- Ibid,

pp. 33-35 .

- Ibid,

p. 37-38 .

- Ibid,

p. 38 .

- Nick Marinello, "The Diaspora," Tulanian, Summer 2006, http:www2.tulane.edu/article_news_details.cfm?ArticleID=6750, accessed 11/01/2006.

- J. Mark Souther, "Into the Big League," Journal Urban History,

Vol. 29 ,No. 6 ,694-725 (2003), Sage Journals Online, http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/29/6/694, accessed 12/05/2008.

- Matt Scallan and John Pope, "Most of City's Workers Fall into Service Jobs - Orleans Poverty Rate Among Worst in U.S.," The Times Picayune, New Orleans, November 20, 2001, National,

p.01 .

- Coleman Warner, "Reconstruction: First School Integration Test Came in 1870s," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, June 15, 1993, National,

p. A16 .

- Alcee Fortier, Louisiana Studies: Literature, Customs and Dialects, History and Education, New Orleans, LA, F.F. Hansell & Bro. (1894),

pp. 267-268 .

- John Smith Kendall, History of New Orleans, Chicago and New York, The Lewis Publishers (1922),

605 pp. ,p. 531 .

- Beatrice M. Field, Mary S. Ingraham, and Amanda R. Rittenhouse, Potpourri: An Assortment of Tulane's People and Places, Aug. 1983, (Additional research, edits and compilation of material, Aug. 2002),

166 pp. ,p. 38 , http://www.tulane.edu/~alumni/potpourri/Potpourri_web.pdf, accessed 01/12/2008.

- Henry Rightor, Editor, Standard History of New Orleans, Louisiana, Chicago, IL: The Lewis Publishing Company (1900)

743 pp .,pp. 240-241 .

- Paul Zielbauer, "Apologizes for Slave-Era Ads," Race and History.com, http://raceandhistory.com/historicalviews/slaveera.htm, accessed 11/20/2006.

- John P. Dyer, Tulane: The Biography of a University 1834-1965, New York and London, Harper & Row Publishers (1966)

370 pp. ,p. 12 .

- William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass, and Public Policy, Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press (1990)

261 pp .

- "Brown vs.The Board of Education of Topeka," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, (See: Note #1), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_v._Board_of_Education, accessed 12/05/2008.

- "J. Skelly Wright," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Skelly_Wright, accessed 12/08/2008.

- Gwendolyn Thompkins, "Today's College Campuses are Diverse but Fragmented," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, November 14, 1993, National,

p. A26 .

- Clarence L. Mohr and Joseph E. Gordon, Tulane: The Emergence of a Modern University 1945-1980, Baton Rouge, LA, Louisiana State University Press (2001)

504 pp. ,p. 138 .

- "Morial Exhibit at Amistad," Tulane University NewWave, July 8, 2008, http://tulane.edu/news/newwave/newssplash_0708.cfm, accessed 07/08/2008.

- Southern Institute for Education and Research, "A House Divided Teaching Guide, 6, City Hall 1963," http://www.southerninstitute.info/civil_rights_education/divided10.html, accessed 12/05/2008.

- Carl Bernofsky, "A Tradition of Discrimination," Tulanelink.com, http://www.tulanelink.com/tulanelink/racist_legacy_01a.htm, accessed 12/28/2008.

- Cheryl V. Cunningham, The Desegregation of Tulane University, A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in History, University of New Orleans, New Orleans, Louisiana, December, 1982,

118 pp. , Tulanelink.com, http://www.tulanelink.com/tulanelink/desegregation_box.htm, accessed 01/05/2009.

- Clarence L. Mohr and Joseph E. Gordon, Tulane: The Emergence of a Modern University 1945-1980, Baton Rouge, LA, Louisiana State University Press (2001)

504 pp. ,p. 240 .

- "Ruby Bridges and Integration of New Orleans Schools," American Experience Program, PBS, Page created December 1, 2006, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/neworleans/peopleevents/e_integration.html, accessed 12/29/2007. See also: Kit Senter, "Students at first integrated school faced hatred," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, January 24, 2009,

Metro, p. 6 . See also: The McDonogh Three; In 1960, three first-grade girls integrated McDonogh No. 19. ..." The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, May 16, 2004,National, p. 19 .

- Nicholas H. Carter, Contesting Cultural Explanations of Poverty: Migration and Economic Development in New Orleans, 1965-1980, [PDF], A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, April 16, 2007,

96 pp. ,p. 13 .

- Chris Kirkham, "Civil Rights Struggle Lives on in La.'s Public Schools - Segregation Rising since Mid-1980s," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, July 29, 2007, National,

p. 01 .

- Brian Thevenot, "Unintended Consequences - By the 1970s, Real Integration Had Come to New Orleans Public Schools, but as Middle-class Families – both Black and White – Fled, the Schools and the City Suffered," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, May 17, 2004, National,

p. 01 .

- Brian Thevenot, "From Resistance to Acceptance - New Orleans Suburbs, Aided by White Flight, Fought Hardest against Integration. But now, some Suburban School Districts Are Exemplars of Successful Integration." The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, May 19, 2004, National,

p. 01 .

- "Metairie, Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metairie,_Louisiana, accessed 12/02/2008.

- Camille Zubrinsky Charles, Chapter 3, "Can We Live Together? Racial Preferences and Neighborhood Outcomes," in: Xavier N. De Souza Briggs and William Julius Wilson, Editors, The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America, Baltimore, MD: Brookings Institution Press (2005),

353 pp. ,p. 54 .

- Nicholas H. Carter, Contesting Cultural Explanations of Poverty: Migration and Economic Development in New Orleans, 1965-1980, [PDF], A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, April 16, 2007,

96 pp. ,p. 4

- "Covington, Louisiana," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.com/wiki/Covington,_Louisiana, accessed 12/16/2008.

- "Jefferson Parish: People & Household Characteristics," Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, http://www.gnocdc.org/jefferson/people.html, accessed 12/02/2008.

- "St. Tammany Parish: People & Household Characteristics," Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, http://www.gnocdc.org/st_tammany/people.html, accessed 12/02/2008.

- Jenny Hurwitz, "Jeff Pupils Will Be Making History - Desegregation Plan Brings Big Changes," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, August 9, 2008, National,

p. 01 .

- Jenny Hurwitz, "Judge Rejects Magnet School Plan - Elementary School Conversion Opposed," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, January 7, 2009, National,

p. 01 .

- "Civil Rights Acts of 1964," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_Rights_Act_of_1964, accessed 12/05/2008.

- Edmund W. Lewis, "A River Runs through It,"The Louisiana Weekly, New Orleans, August 21-27, 2006,

p. 4 .

- Jennifer Evans, "SCLC Chief Blasts Racism in New Orleans - Civil Rights Group Wraps up Convention," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, July 31, 2008, Metro,

p. 02 .

- (37) Kathleen Morgan, Scott Morgan, and. Rachel Boba, "2008 City Crime Rankings (Continued)," and "An Important Note about New Orleans," in: City Crime Rankings 2008-2009, CQ Press, Washington, D.C., (2008),

417 pp. , http://www.cqpress.com/product/City-Crime-Rankings-2008.htm, accessed 01/12/2009.

- Brendan McCarthy, "Overall N.O. Crime Rate Leads U.S., Study Says - Not My Fault, Riley Replies," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, November 25, 2008, Metro,

p. 01 .

- Christine Harvey, "Wider Causeway Boulevard on Way - New Lane on Each Side Should Be Done by End of Year," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, January 7, 2009, National,

p. 01 .

Web site created November, 1998 This section last modified August, 2010

| Home Page | Site Map | About Bernofsky | Curriculum Vitae | Lawsuits | Case Calendar |

| Judicial Misconduct | Judicial Reform | Contact | Interviews | Disclaimer |

This Web site is not associated with Tulane University or its affiliates

© 1998-2015 Carl Bernofsky - All rights reserved