|

Of all complaints filed against judges for misconduct during the -- From data compiled in 2007 by

Dr. Richard Cordero |

Federal Judiciary has Discipline Problem

The federal judiciary has a discipline problem — its own.

Adjudicating misconduct complaints against federal judges is swathed in secrecy, lacks uniform rules across the nation and begets retaliation against complaining lawyers.

As for bullying behavior from the bench, reprimands for judicial intemperance toward counsel or their clients is nearly nonexistent, although it violates judicial canons.

An examination by the National Law Journal, a Daily Business Review affiliate, of the issue of abusive judges and interviews with ethics experts about the known discipline cases shows a set of reform proposals may do little to increase judicial accountability, make the system more transparent or insulate those who step forward to complain.

Also, five years after the Judicial Conference recommended that the 13 federal circuits post discipline orders online, only two — the 7th and 9th — have followed through.

The proposals, which include replacing decentralized circuit rules with national standards and empowering a national conduct committee to see all complaints filed, are up for full review March 11 by the Judicial Conference of the United States, the policymaking arm of the federal judiciary.

"What bothers me about [the lack of transparency] is that it is very destructive for a judiciary that is under attack," said Mark I. Harrison, an attorney at Phoenix's Osborn Maledon who chaired the American Bar Association commission evaluating the Model Code of Judicial Conduct for state courts.

"Here they are functioning like an old boys' network," he said. "It is very distressing they are not making the process transparent."

Punishment to misconduct by federal judges remains highly confidential. When news leaks out, it can be sensational and embarrassing for the judiciary — but produces negligible change.

In Galveston, Texas, U.S. District Judge Samuel B. Kent returned to work Jan. 3 after a four-month paid suspension following a 5th Circuit Judicial Council finding of sexual harassment of a female employee. Kent was transferred to Houston, but so was his accuser. Kent did not return calls seeking comment.

U.S. District Judge Manuel Real of Los Angeles defended himself in an April 2006 impeachment hearing on allegations that he interfered in a bankruptcy case to help a woman whose parole he supervised. The complaint against him was twice tossed out by the chief 9th Circuit judge, who ended up issuing a public reprimand.

In January, the national conduct committee, a subcommittee of the Judicial Conference, upheld that action but sent the case back to the 9th Circuit for reconsideration of a separate, private admonishment of Real.

The judge was accused of a pattern — in 72 cases over many years — of not providing reasons for decisions when required. Real did not return calls seeking comment.

The proposed rules still don't clarify how aggressive the national conduct committee would be when circuit councils dismiss credible complaints without investigation, according to Arthur Hellman, a professor at University of Pittsburgh School of Law who has written extensively on judicial ethics.

He said he could imagine a faceoff between circuits around the country and the national committee over its assertion of authority. "The prospect of reopening an otherwise closed proceeding does have the potential for these ugly disputes," he warned.

Ethics specialist Carol Langford, who defends professionals in discipline proceedings in California and teaches at the University of California Hastings College of the Law, chafed at the lack of transparency in the system.

The fact that discipline orders do not identify judges unless a public censure is issued "is not right," Langford said. "It is a federal judge. They should say the name. People should know that. We're paying for them, and we have a right to know who has been disciplined."

The addition of more oversight at a national level may appease people, but it must be done by people who understand oversight — not simply by other judges who don't know the discipline process, she said.

In the first 191 years after the creation of the federal judiciary in 1789, impeachment and removal from office was the only means of punishing misconduct by federal judges, who are appointed for life.

In that period, only 10 judges were impeached by the U.S. House. Two of them resigned before a Senate trial, four were acquitted, and four were convicted and removed.

The mechanism for disciplining federal judges for misconduct is relatively new, created just 27 years ago with the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980. The act authorized punishment for misconduct that did not rise to the level of impeachable offense. It allowed each circuit to establish its own disciplinary rules, investigate alleged misconduct and impose sanctions up to temporary suspension of a judge.

After passage, another five judges were convicted of crimes while serving as judges. Three were impeached and removed; the other two resigned.

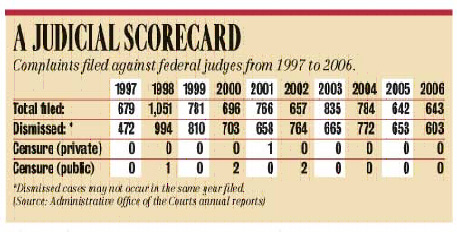

During the decade ending last year, there were 7,534 complaints filed against federal judges, magistrates and bankruptcy judges, but in that time just five public censures and one private censure were issued, according to the judiciary's own statistics. A total of 7,099 were dismissed. There are a total of about 900 federal district and appellate judges.

From 2001 to 2005, chief judges appointed nine special committees to investigate 15 complaints against nine judges, according to a 2006 study of circuit enforcement. Chief judges dismissed six complaints and imposed public censure on two judges and private censure on one.

Censure refers to any harsh criticism of a judge's conduct; if private it is shared only with the judge who is admonished. Public censure results from a final order placed in the circuit court clerk's office, where it can be viewed by the public.

To be sure, the majority of complaints are dismissed as frivolous or the result of disgruntled litigants unhappy with the outcome of their cases, according to statistics from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

But problems have been found in the handling of the some of the most contentious, high-visibility cases including errors in processing complaints and inaccuracies in circuit reporting of statistics.

The 2006 report concluded most complaints against judges were handled appropriately, but circuit chief judges sometimes dismissed complaints even when more investigation was justified.

In examining a small sample of 17 high-visibility cases, the report found a "far too high" percentage — nearly 30 percent — were mishandled.

An example of a mishandled discipline claim involved a 2002 complaint against 7th Circuit Judge Richard D. Cudahy, who revealed to a reporter on the eve of Vice President Al Gore's acceptance of the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 2000 that Independent Counsel Robert W. Ray had impaneled a new grand jury to investigate President Bill Clinton.

Gore supporters complained the unidentified source of the report may have disclosed the grand jury proceeding for political gain. Cudahy waited 24 hours to come forward as the leaker. The complaint was dismissed based on the judge's corrective action. The 2006 report found that dismissal of the complaint without some investigation was inconsistent with discipline standards.

In a larger sample of 593 cases that all had merit, the study found 25, or 4 percent, had "problematic" handling. Problems arose largely because chief judges failed to make adequate inquiries before dismissing allegations.

The study also reported a 2 percent to 3 percent error rate in processing complaints, which it said was not a serious flaw. In addition, it noted that checking misconduct dispositions against case files showed reporting errors that underreported matters to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

The study's review of the 593 files revealed the appointment of six special investigative committees from 2001 to 2003, but data from the circuits themselves reported only one such committee. Also, the circuits did not tell the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts how often they conducted limited inquiries into complaints, the study found.

Facing pressure from Congress, the Judicial Conference of the United States initiated disciplinary reforms drawn from the report's recommendations. The plan drafted by the Judicial Conference's seven-member Conduct Committee headed by 2nd Circuit Judge Ralph K. Winter is up for review March 11.

The reform proposals would replace the decentralized system of circuit self-regulation established by the 1980 discipline act with mandatory national standards. This mirrors a failed 2006 plan introduced by U.S. Rep. James Sensenbrenner, R-Wis., to create an inspector general to oversee the courts and report misconduct to Congress.

"In both hearings, on Sensenbrenner's inspector general bill and on the [Judge Manuel] Real impeachment, just below the surface in both was the question: 'Is the judiciary doing enough to impose discipline?'" Hellman said. "The inspector general was kind of a warning shot; if the judiciary doesn't do it then Congress will."

By contrast, every state court in the nation has some system of discipline, and nearly all are relatively transparent, beginning with California, which instituted the first disciplinary scheme in 1960. It routinely admonishes judges for caustic behavior on the bench as well as more serious ethical violations.

From 1990 to 1999, the California Commission on Judicial Performance disciplined 499 judges.

"From where I sit, the states are light-years ahead of the federal judiciary," said Charles Geyh, a professor at Indiana University School of Law — Bloomington who studies judicial ethics and discipline. He said current problems reach back to the 2005 congressional proposal to assign an inspector general as a watchdog on the judiciary. "The driving force behind that proposal was precisely that the judiciary was not taking discipline seriously and precisely because it was decentralized," Geyh said.

The Judicial Council has been clear that breach of the judicial code of conduct isn't enough to merit punishment. The misconduct has to be something more, said Douglas Kendall, executive director of Community Rights Counsel in Washington, which pushed for ethics reforms requiring judges to report paid trips to private seminars.

Unlike many mandatory state codes of judicial conduct, the federal code of conduct is aspirational, saying judges "should" follow the canons.

Even under the proposed rules, a judge subject to a complaint sees it immediately and learns who complained. That differs from many state misconduct proceedings, which initially protect the privacy of the complainant as well as the judge. The proposed changes do not allow anonymous complaints.

From: Daily Business Review, "Justice Watch," February 25, 2008, http://www.dailybusinessnews.com/..., accessed 02/25/08. Pamela A. MacLean reports for the National Law Journal, an ALM Media affiliate of the Daily Business Review. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C.

|

|

|